Welcome to the EGGhead Forum - a great place to visit and packed with tips and EGGspert advice! You can also join the conversation and get more information and amazing kamado recipes by following Big Green Egg to Experience our World of Flavor™ at:

Want to see how the EGG is made? Click to Watch

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Pinterest | Youtube | Vimeo

Share your photos by tagging us and using the hashtag #BigGreenEgg.

Share your photos by tagging us and using the hashtag #BigGreenEgg.

Want to see how the EGG is made? Click to Watch

Calibration 101

Jeffersonian

Posts: 4,244

There was a rather lively thread the other night about the checking and adjustment of dial-type bimetal dome thermometers like this one:

As we say in the electrical engineering biz, the thread wound up with a pretty low signal-to-noise ratio, so to clear the air about the topic of calibration, and at no small risk of recurring volcanic activity, here's a short primer on calibration and what can - and cannot - be done to improve the performance of one's Egg temperature instrumentation.

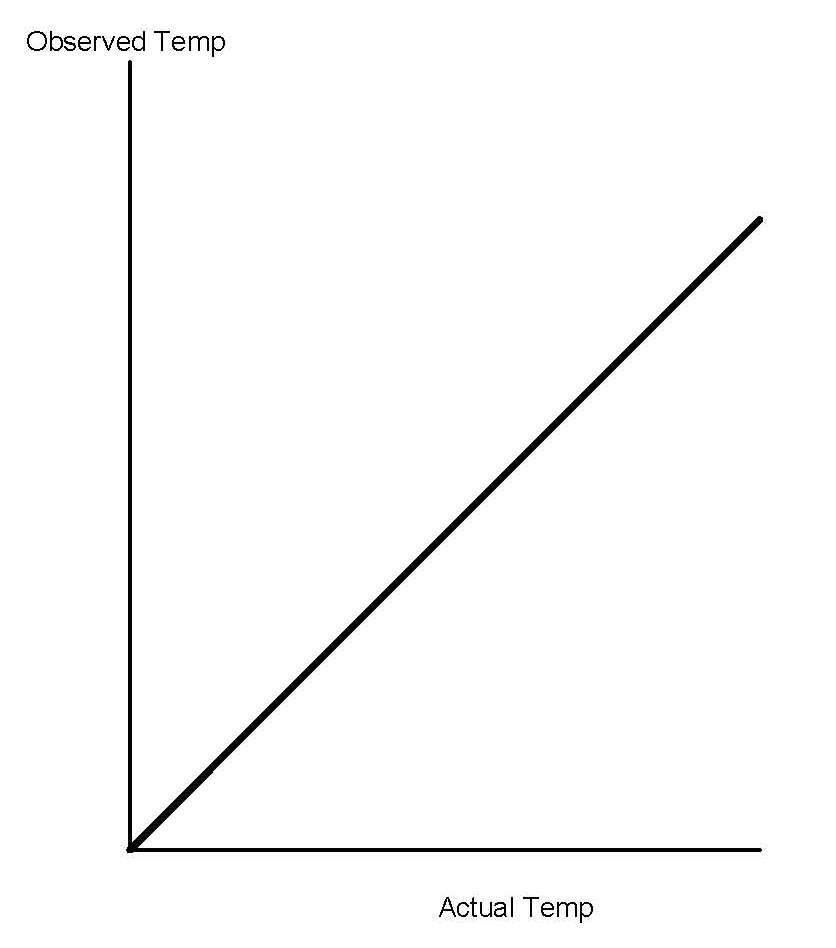

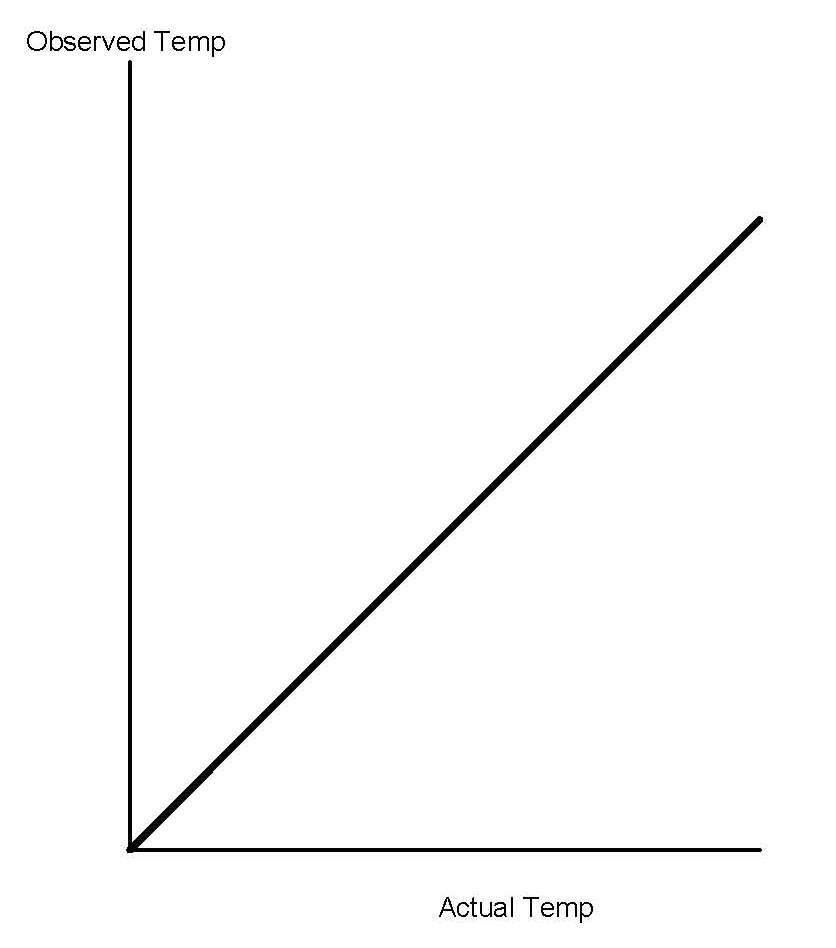

First, let's define what calibration is in our case. Calibration is the adjustment of an instrument's available performance parameters in order to make it accurately reflect a process characteristic. In this case, our characteristic is dome temperature and the objective is to make our thermometers read the temperature of the BGE dome to within an acceptable tolerance. If we were to check our thermometers using a known temperature standard and plot the results on a simple x-y graph, the ideal would be a straight line, much like the graph below:

I didn't scale this, but you can see the line slopes upward to the right, with one degree of actual temperature change in the Egg registering as one degree of change on the thermometer. The heavy sloped line lays perfectly over the "ideal" line.

Small Errors

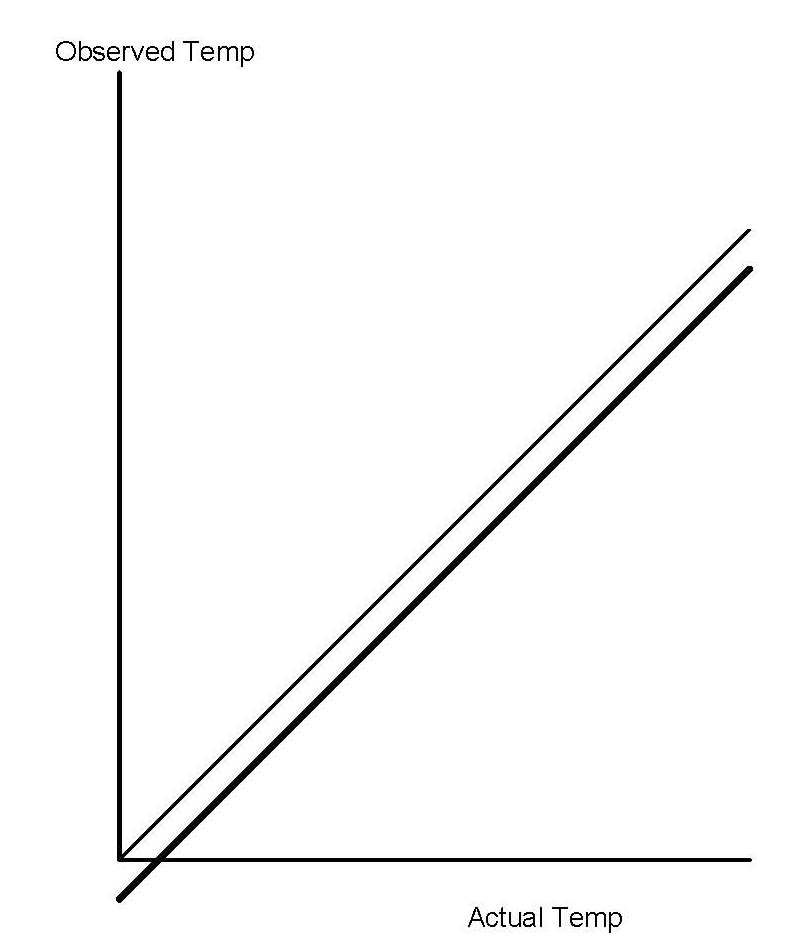

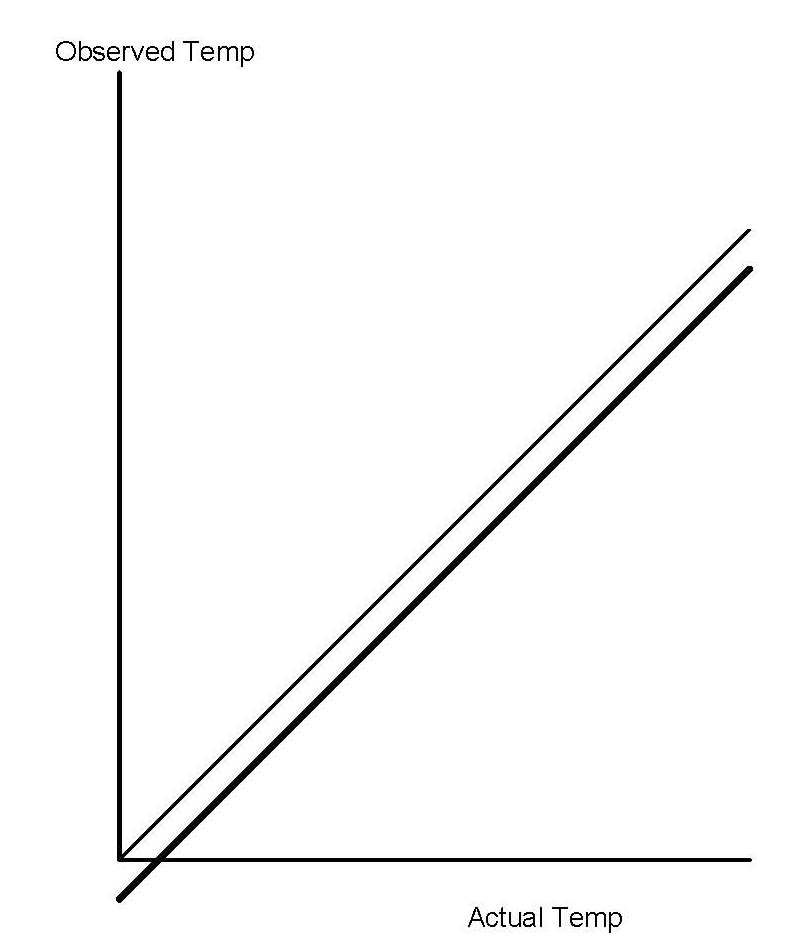

Unhappily, our thermometers do not always perform ideally, sometimes requiring adjustment or replacement. One way a thermometer exhibits error is to develop an offset, as shown in the graph below:

As you can see, this thermometer's response has shifted a small amount over the useful range, let's say 10*F. A reading of 250 on the dial means the dome is at 260*, 350* means 360*, etc. Usually, this is detected using boiling water, around 212*F and the deviation found is assumed to be just this sort of offset, i.e. an error that is consistent over the displayed range. The remedy is to turn the nut on the back of the thermometer until it reads 212* when dunked in the 212* water and, when small deviations like this are found, it probably does the trick.

This is known as "zeroing" an instrument, and it's the only arrow we have in our quiver to fix these thermometers. Keep that in mind: We can only adjust the nuts on the rear of the units, moving the heavy line up and down.

Larger Errors

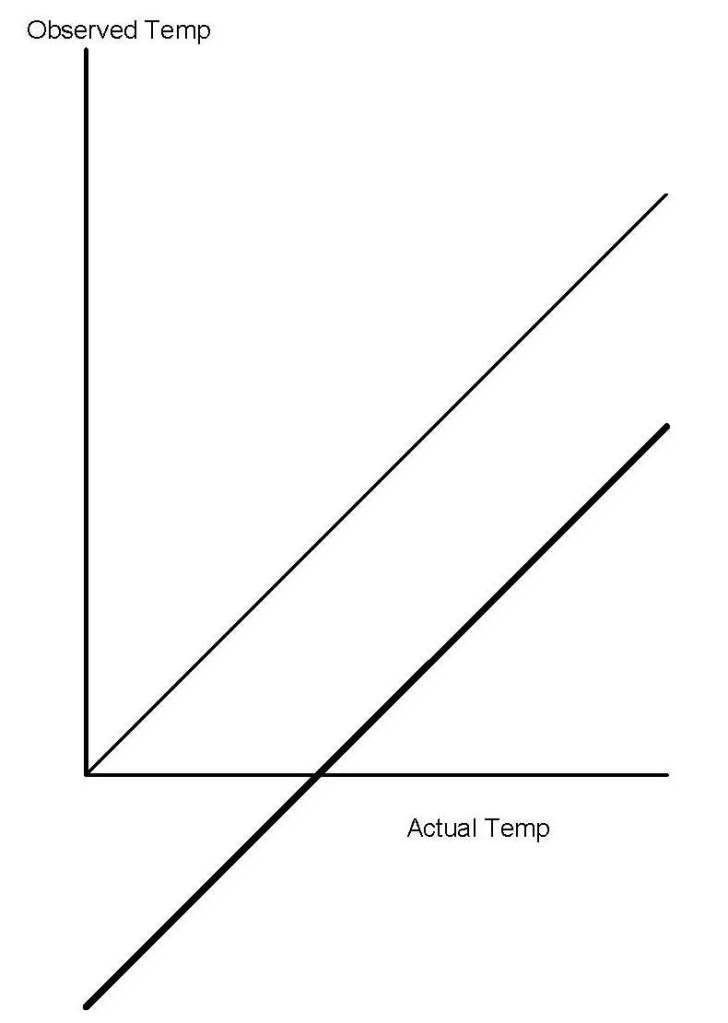

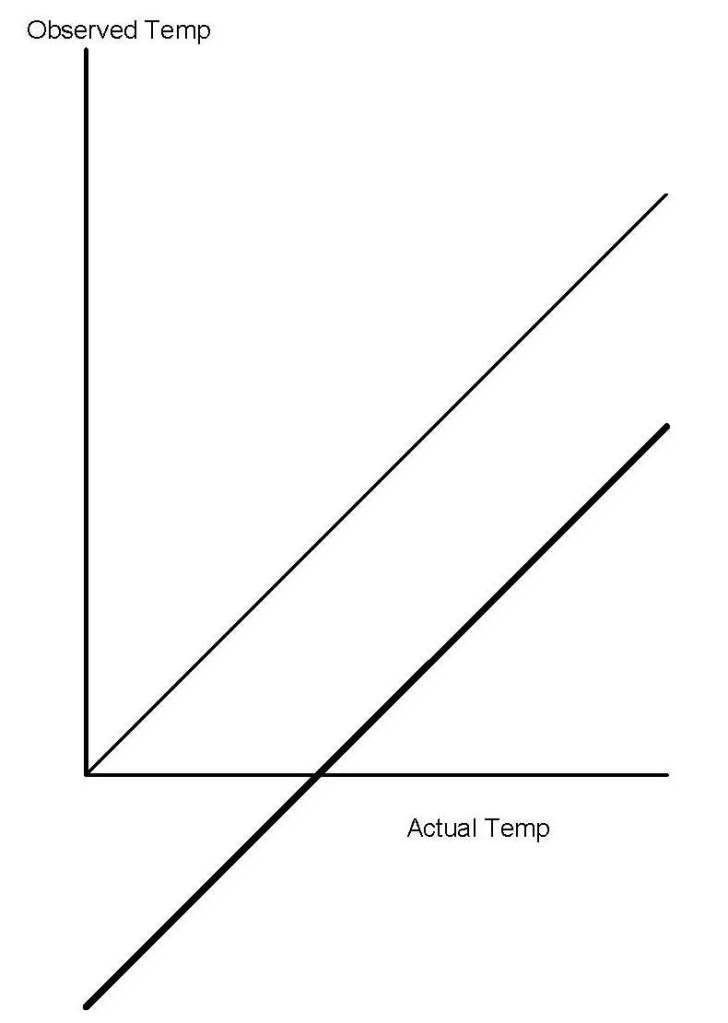

The same sort of error, but of a different scale, is shown below:

Here, the error detected when we plop the thermometer into boiling water may be very large relative to the temperature being measured. The member who started the aforementioned thread found a ~70* error, for example. The graph actually overstates the information extracted from the boiling water test, since the only thing we are sure of is that the reading is ~70* low at 212*. We just assume that it's 70* across the range of the instrument.

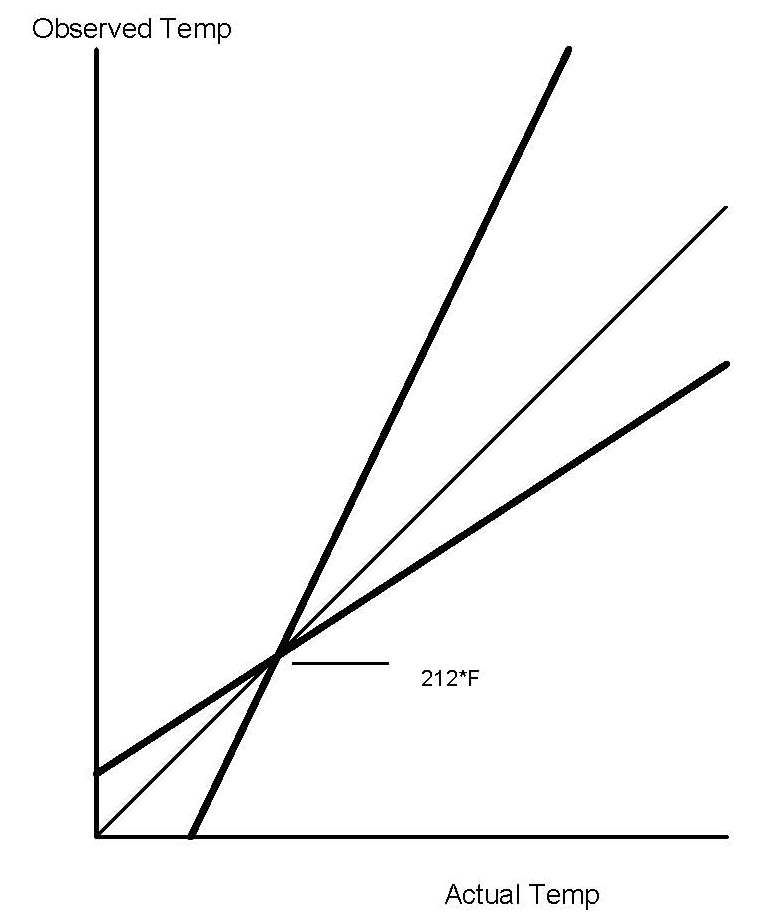

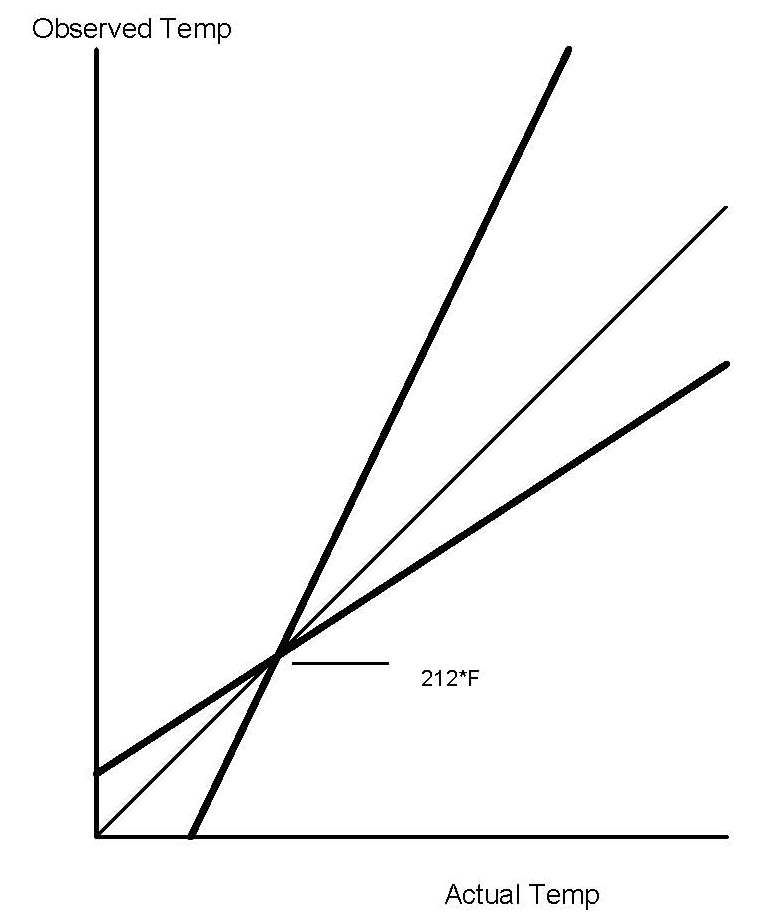

We can, of course, adjust the nut so the meter reads 212* and go on assuming everything is okay, but it's more likely that the 70* deviation is symptomatic of a deeper problem and there is something wrong with the unit and it should be tested to make sure it's not acting like one of the heavy lines on this graph:

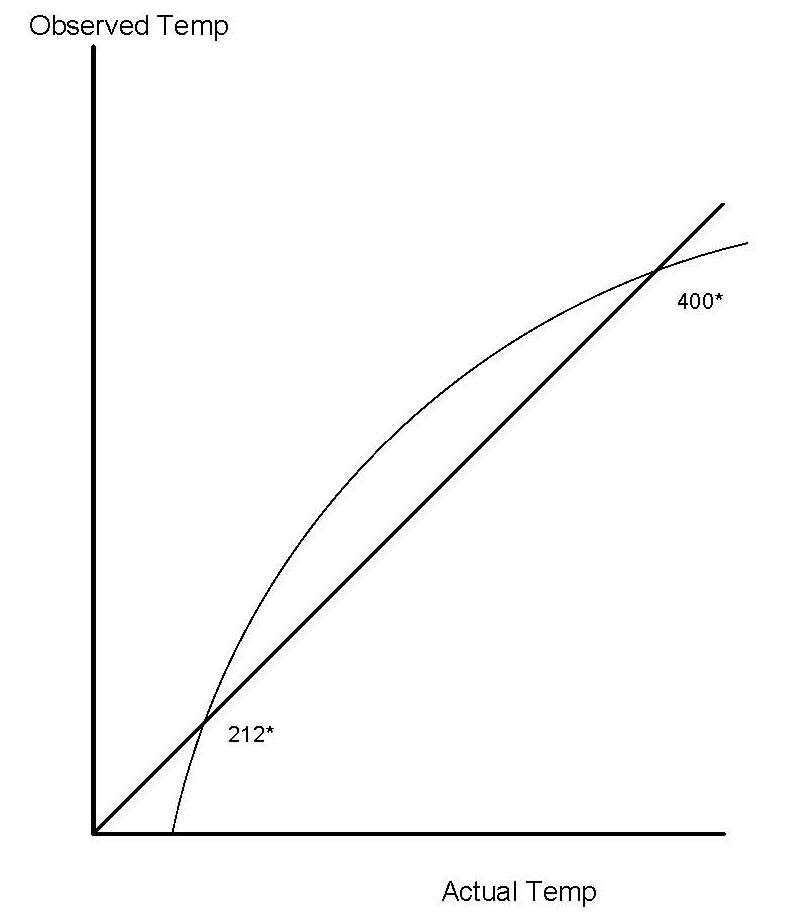

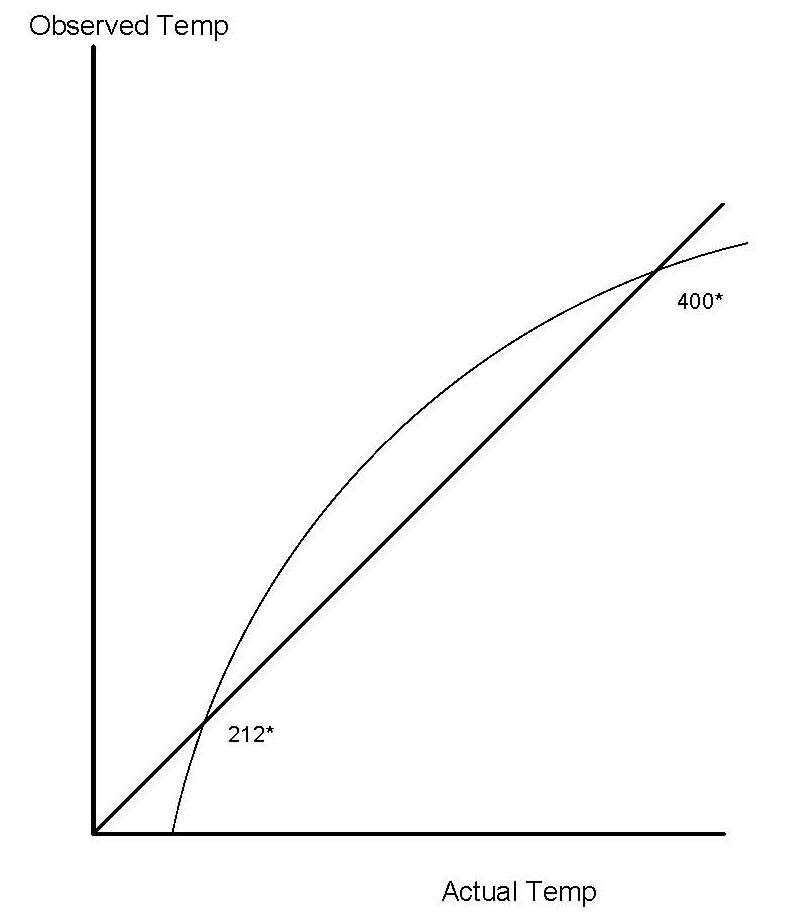

As you can see, each of these "calibrations" resulted in a reading of 212* in boiling water, but each will result in a gradually greater error as one increases dome temperature. The responses are still linear (they are straight lines, after all), but the slopes of the lines are such that they only produce erroneous results outside of a very small band. Worse, the Egger will never know what went wrong, believing his or her dome temp to be "calibrated." Worse yet, the response might be like this:

How to dig deeper

To see if your thermometer is accurate at some point other than 212*, you'll need two things: A heat source and a reasonably accurate reference temperture sensor to compare your dome thermometer to. Fortunately, we all have the Egg to use as a temperature chamber and I've used this cheap Accu-Rite digital as my reference:

It's about $12 at Walmart, has a probe that is thin and long enough to slip into the same hole at the dome unit and is, as a thermocouple instrument, accurate to within 3* or so. Not instrumentation-grade calibration equipment, but it's a lot cheaper than a Fluke calibrator and is close enough for our purposes.

The process is straightforward: Simply bring your Egg up to a certain temp, stabilize it, and read the dome temp with the dial thermometer. Then slip the dome unit out and put in the digital's probe, allowing it to settle. Record both readings. Repeat that process over several temperatures, minding the maximum range of the digital (I think it goes up to 392*F, or 200*C). Finally, make a simple x-y plot of the readings with the digital's figures on the x-axis and the dial thermo's on the y-axis. Draw a best-fit line through the points you've plotted.

If the line you've drawn is on top of, or parallel to, the "ideal" line, then congratulations, your unit can be zeroed successfully by turning the nut. You can even do it at your Egg using the digital, in case you don't feel like boiling water.

If the line isn't parallel to the ideal, then you may have a problem. Should the slope be not too different from the ideal, you can use Egg to center the point at which the two lines cross over some temperature that you use a lot, in exactly the same way you'd do it with boiling water. If you do a lot of low-n-slow cooks, this might be around 250*. If you do more high-temp cooking, shoot for something in that range. The important thing is to minimize the reading error in the range you use most.

If the slope of the line is a lot different from the ideal, you're likely out of luck. As mentioned above, we can only move these lines up and down on the graph...we cannot change the slopes of the lines (at least I don't know how). Chuck the thermometer and get a new one. You might even be able to use the digital for low-n-slow cooks in the meantime, as I've done many times.

Large food and beverage firms I deal with calibrate their critical points - ovens, coolers, etc. - on a quarterly basis. This is high-quality, high-cost instrumentation, and it needs tending that frequently. Pharmaceutical firms have even shorter calibration intervals. Given that your dome thermometer is the only thing standing between you and food that either takes forever to cook or is scorched to a cinder in a fraction of the time it should be cooked to perfection, it makes sense to pay attention to what it's doing.

As we say in the electrical engineering biz, the thread wound up with a pretty low signal-to-noise ratio, so to clear the air about the topic of calibration, and at no small risk of recurring volcanic activity, here's a short primer on calibration and what can - and cannot - be done to improve the performance of one's Egg temperature instrumentation.

First, let's define what calibration is in our case. Calibration is the adjustment of an instrument's available performance parameters in order to make it accurately reflect a process characteristic. In this case, our characteristic is dome temperature and the objective is to make our thermometers read the temperature of the BGE dome to within an acceptable tolerance. If we were to check our thermometers using a known temperature standard and plot the results on a simple x-y graph, the ideal would be a straight line, much like the graph below:

I didn't scale this, but you can see the line slopes upward to the right, with one degree of actual temperature change in the Egg registering as one degree of change on the thermometer. The heavy sloped line lays perfectly over the "ideal" line.

Small Errors

Unhappily, our thermometers do not always perform ideally, sometimes requiring adjustment or replacement. One way a thermometer exhibits error is to develop an offset, as shown in the graph below:

As you can see, this thermometer's response has shifted a small amount over the useful range, let's say 10*F. A reading of 250 on the dial means the dome is at 260*, 350* means 360*, etc. Usually, this is detected using boiling water, around 212*F and the deviation found is assumed to be just this sort of offset, i.e. an error that is consistent over the displayed range. The remedy is to turn the nut on the back of the thermometer until it reads 212* when dunked in the 212* water and, when small deviations like this are found, it probably does the trick.

This is known as "zeroing" an instrument, and it's the only arrow we have in our quiver to fix these thermometers. Keep that in mind: We can only adjust the nuts on the rear of the units, moving the heavy line up and down.

Larger Errors

The same sort of error, but of a different scale, is shown below:

Here, the error detected when we plop the thermometer into boiling water may be very large relative to the temperature being measured. The member who started the aforementioned thread found a ~70* error, for example. The graph actually overstates the information extracted from the boiling water test, since the only thing we are sure of is that the reading is ~70* low at 212*. We just assume that it's 70* across the range of the instrument.

We can, of course, adjust the nut so the meter reads 212* and go on assuming everything is okay, but it's more likely that the 70* deviation is symptomatic of a deeper problem and there is something wrong with the unit and it should be tested to make sure it's not acting like one of the heavy lines on this graph:

As you can see, each of these "calibrations" resulted in a reading of 212* in boiling water, but each will result in a gradually greater error as one increases dome temperature. The responses are still linear (they are straight lines, after all), but the slopes of the lines are such that they only produce erroneous results outside of a very small band. Worse, the Egger will never know what went wrong, believing his or her dome temp to be "calibrated." Worse yet, the response might be like this:

How to dig deeper

To see if your thermometer is accurate at some point other than 212*, you'll need two things: A heat source and a reasonably accurate reference temperture sensor to compare your dome thermometer to. Fortunately, we all have the Egg to use as a temperature chamber and I've used this cheap Accu-Rite digital as my reference:

It's about $12 at Walmart, has a probe that is thin and long enough to slip into the same hole at the dome unit and is, as a thermocouple instrument, accurate to within 3* or so. Not instrumentation-grade calibration equipment, but it's a lot cheaper than a Fluke calibrator and is close enough for our purposes.

The process is straightforward: Simply bring your Egg up to a certain temp, stabilize it, and read the dome temp with the dial thermometer. Then slip the dome unit out and put in the digital's probe, allowing it to settle. Record both readings. Repeat that process over several temperatures, minding the maximum range of the digital (I think it goes up to 392*F, or 200*C). Finally, make a simple x-y plot of the readings with the digital's figures on the x-axis and the dial thermo's on the y-axis. Draw a best-fit line through the points you've plotted.

If the line you've drawn is on top of, or parallel to, the "ideal" line, then congratulations, your unit can be zeroed successfully by turning the nut. You can even do it at your Egg using the digital, in case you don't feel like boiling water.

If the line isn't parallel to the ideal, then you may have a problem. Should the slope be not too different from the ideal, you can use Egg to center the point at which the two lines cross over some temperature that you use a lot, in exactly the same way you'd do it with boiling water. If you do a lot of low-n-slow cooks, this might be around 250*. If you do more high-temp cooking, shoot for something in that range. The important thing is to minimize the reading error in the range you use most.

If the slope of the line is a lot different from the ideal, you're likely out of luck. As mentioned above, we can only move these lines up and down on the graph...we cannot change the slopes of the lines (at least I don't know how). Chuck the thermometer and get a new one. You might even be able to use the digital for low-n-slow cooks in the meantime, as I've done many times.

Large food and beverage firms I deal with calibrate their critical points - ovens, coolers, etc. - on a quarterly basis. This is high-quality, high-cost instrumentation, and it needs tending that frequently. Pharmaceutical firms have even shorter calibration intervals. Given that your dome thermometer is the only thing standing between you and food that either takes forever to cook or is scorched to a cinder in a fraction of the time it should be cooked to perfection, it makes sense to pay attention to what it's doing.

Comments

-

Brad,

Low Voltage Differential Transducers? :laugh:

SteveSteve

Caledon, ON

-

Linear Variable...

And, take it from a guy who had to fit a ninth-order polynomial to its output, they ain't always as linear as you'd like. -

Dude...it's a grill. Baking aside, as long as you're within 50 degrees whatever you're cooking is going to be fine.

With a little experience a person should know if their thermo is off by more than 50 degrees. Honestly, a lot of cooks I do I don't even pay attention to the thermometer. I guess it goes back to my days using open pits and kettle style cookers. They don't even have thermometers. -

thanks - I think, but I snoozed off 6 minutes into reading your post. One of the key things about those thermometers is removing and PITCHING those unneeded inside spring clips!Re-gasketing the USA one yard at a time

-

-

we are cooking not doing experiments.....and in due time everyone here will either already know or soon learn when their food is done no matter what any thermometer says...get OFF the soapbox..

-

I have a headache.

__________________________________________Dripping Springs, Texas.Just west of Austintatious

__________________________________________Dripping Springs, Texas.Just west of Austintatious -

you're so insensitive

-

I think since I started all of this discussion that the matter would best be solved by cooking more ribs and posting the pic's. I'm thinking now that I may have very well changed the calibration by twisting the thermo on the egg with the tight clip on. I never would of known that it would be so easy to change. I also checked the flux capacitor and I believe all is in order now. :laugh:

-

Probably true..but I wanna go skydivin with ya..LOL....really it's all a result of my recent snorkelling...LMAO..

-

-

Baking aside, as long as you're within 50 degrees whatever you're cooking is going to be fine.

Rod, please. Are you saying you don't care if your ribs are on at 201* or 299*?

My post is offered as a tutorial. If you don't want to follow it, that's cool. -

I think you should give him your forum handle...then again..whadda I NO

-

That's a bit more than 50° isn't it?

If you're set at 212, where low and slow matters, you'll be reasonably close.

If you're cooking pork chops and are shooting for 400 and you happen to be at 430, I'm guessing you'd never know the difference in the end product. -

I think I can't cook now.

I think I can't cook now.

Mike -

That's a bit more than 50° isn't it?

Not according to my figgerin'...if you're looking for a temp of 250, 201 and 299 are both "within" 50 degrees of it.

Lots of people have posted recipes that start out at 225, bump to 250, then finish at 275. If 50 degrees doesn't matter, then are these folks all just spinning their wheels?

My post was intended as a Joe-Friday, just-the-facts-ma'am tutorial. Why is this about personalities? -

Who said anything about personalities? You taking it personally?

I misunderstood your last post about the 201-299 range. Semantics really.

Like I said, if your thermo is reasonably close at boiling point, it will be reasonably close at 250. The variation isn't going to swing wildly inside of a 40 degree range. -

Could you ever?

Sorry Mike, too easy. You toss softballs, I'm swinging for the fences.

I'm evil. I hate myself. -

Sorry Wess, my post was intended for those familiar with middle-school math. I'll see if Babblefish can translate it into something simpler for you.

-

cause your personality comes across...just screamin ****..quit tryin to turn bbq into a scientific experiment or argument...we are cookin pig...as I already said..if you want to argue with engineers go find their forum..let us continue cookin at 219.8375° or dare I say 283.98356° who gives a sh!t...dome therm says 235° thats good enough for me.....when its done it's done..please stop drawing every post you either start or reply to into a week long friggin soap opera..remember food safety........this will be my last reply to any of your posts...I may be an ****...but you my friend are an ass...

-

see below..since this was ahead of my post..no need for you to bother..

-

What to go skydiving with me next week, you go first.

Mike -

Talk about projection...sheesh. But there is a God, and He is merciful:this will be my last reply to any of your posts

-

I'm in..always wanted to..but was also a little less heavy..LOL

-

I normally have to turn it with a wrench of some sort, but I suppose it's possible. Good to hear you're back to cookin', LME.

-

You better not...I'm still planning on getting a posse from STL to attend your grand opening.

-

FWIW, i don't think i said anything last night that doesn't agree with this entirely.

the part that i took issue with wasn't mentioned here, and i won't revisit it. i'll just say that you are pretty correct in all of this. i don't think anyone disagrees with it frankly.

i'm not sure that i, personally, am expecting, or even need, this level of accuracy. if i did, i wouldn't be using a bimetallic thermometer perhaps, from any manufacturer.

if there's anything in what i said last night that gave you the impression i'd be in disagreement with the logic here, then i'd say i was misunderstood.

because what i was pooh poohing had nothing to do with what calibration is, or how a bimetallic thermometer might be damaged to the point where you could "calibrate" to a single point, and still be off at some other temperature. i never disagreed with that. i in fact mentioned it myself.

there's a lot of work here. and since it doesn't bring up the point from last night on which we differed, i'll simply say thanks for the effort. -

now if we could just get you to promise the same about pinging!

(just kidding, wess. don't go nutty on me...) :ermm: -

Thank you, Jeff. It's the spirit in which it was offered. Now insult me so we can have some fun. :woohoo:

-

well.

i'm sorry if anything i said last night was taken as a direct insult.

i know i was thinking it, but if i really did call you "a ham-headed, thimble-d!cked, half-wit knob-jockey" my only defense is that i thought i'd canceled it before hitting "submit". :huh:

>kidding, lest panties become knotted by any or all

Categories

- All Categories

- 184K EggHead Forum

- 16.1K Forum List

- 461 EGGtoberfest

- 1.9K Forum Feedback

- 10.5K Off Topic

- 2.4K EGG Table Forum

- 1 Rules & Disclaimer

- 9.2K Cookbook

- 15 Valentines Day

- 118 Holiday Recipes

- 348 Appetizers

- 521 Baking

- 2.5K Beef

- 90 Desserts

- 167 Lamb

- 2.4K Pork

- 1.5K Poultry

- 33 Salads and Dressings

- 322 Sauces, Rubs, Marinades

- 548 Seafood

- 175 Sides

- 122 Soups, Stews, Chilis

- 40 Vegetarian

- 103 Vegetables

- 315 Health

- 293 Weight Loss Forum